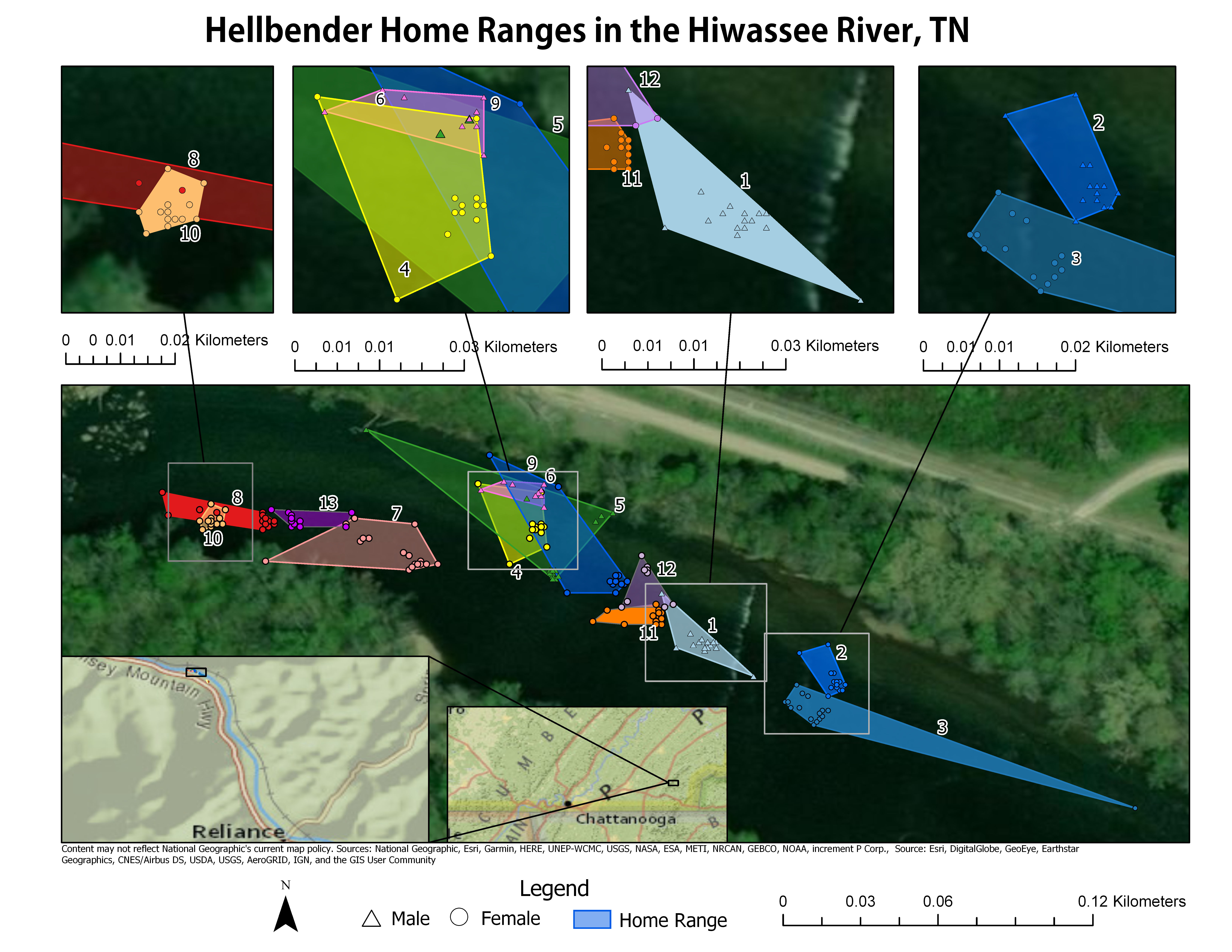

This time of year as the semester draws to a close and the temperatures continue to plummet, we begin to take a break from our regular field work out in the streams. This is partly due to the fact that the hellbenders tend to settle down around this time of year, picking a rock to hang out under until the temperature starts to warm up again in the spring. The other part is due to the fact that it can be dangerous for us to monitor for the hellbenders when it is this cold, particularly in the Hiwassee where we have to don wetsuits in order to track them. We don’t want to get hypothermia! Brrrr.

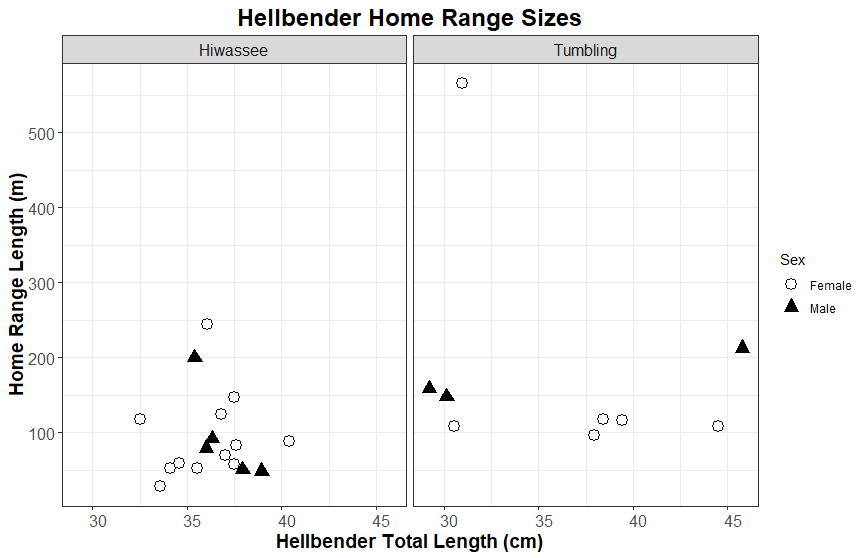

We do plan to return back to East Tennessee opportunistically throughout the winter, to try to check up on the salamanders at least once a month. This will allow us to add to the popular literature showing that they don’t move as much during the winter, assuming that is in fact what we find. It will be easier to survey Tumbling creek in the winter, since at least there we don’t need to use wetsuits. The water is colder than the Hiwassee, but it is shallower – so as long as we don’t slip and fall, we can do it without getting wet. Unfortunately, falling does happen!

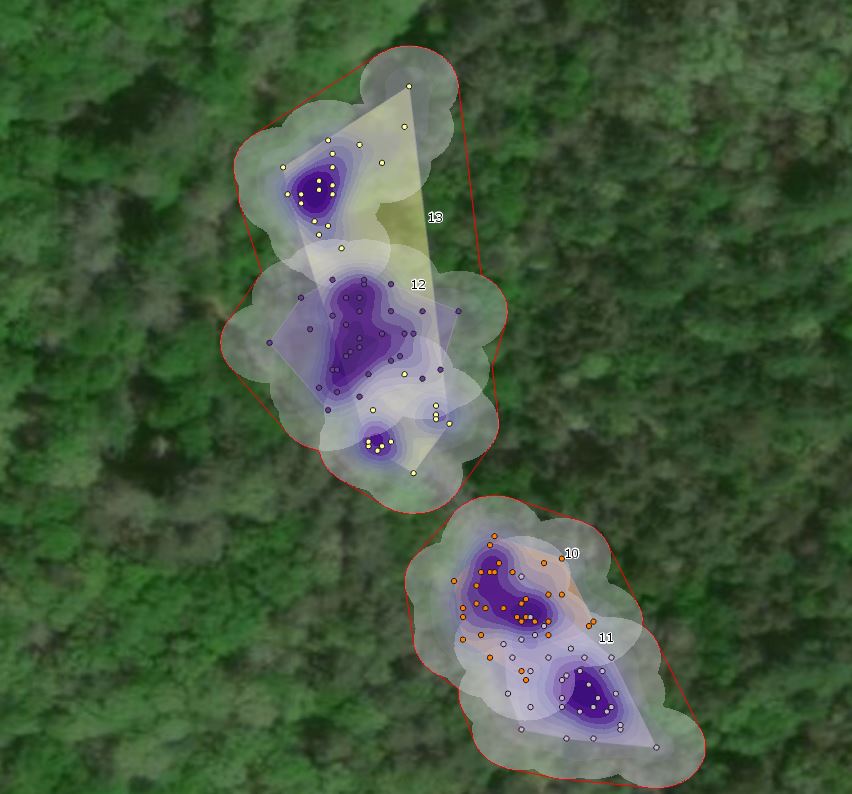

Meanwhile, when I’m not freezing out in the field – I’ll spend the rest of my time over the winter break reading over more literature about analyzing animal movements, a subject that volumes of articles have been written about. For now, I have been playing around with using kernel densities in Arc GIS Pro to analyze core home range sizes. This approach tells more about where the animals chose to spend the majority of their time. Unlike minimum convex polygons, which simply outline the entire extent that an animal may use – kernel densities focus on highlighting areas that are most important to the animal.

So far, our findings seem toindicate that when using kernel densities to determine the home ranges of thehellbenders, they have a very limited area that they tend to utilize most ofthe time. This makes sense, since hellbenders are largely sedentary throughoutthe year (with mating season in the fall being an exception). I haven’t had the chance to compare too many differences between Tumbling and Hiwassee – but upon first inspection it appears the home ranges in Tumbling are slightly larger than in Hiwassee. This fits with the amount of movement we saw in the Tumbling animals compared to those at Hiwassee, which often times were under the same rocks. This photo below shows an example of some kernel density home ranges in Tumbling creek. It is interesting to see how kernel densities can highlight the fact that while home ranges may appear overlapping with minimum convex polygons (e.g. 12 & 13), in reality when looking at the spatial use with kernel density analysis we see that 13 has used an area upstream and downstream of 12’s home range – but they did not generally overlap.

By the time the spring rolls around, I hope to have done a fair bit of analysis on my data – so that it can be useful for predicting where to release our hellbenders for the best results. Furthermore, the data collected from these two streams will help us to compare the results from our translocation in order to understand the level of “success”. Granted, this is relative – since we are only able to track these animals for 2 years before the transmitters die. After that, we hope that the translocated individuals will reproduce and start to increase the populations in the streams where we are releasing them. Only time will tell! Stay tuned for more updates as the seasons change yet again. Until then, stay warm!